Warning: this article contains spoilers

Therapeutic aspect 1: The healing value of the ‘ kindly observing self’

Central to Frank Capra’s Christmas parable It’s a Wonderful Life (1946) is its beginning. The viewer is confronted by a vision of a black and white universe and the sound of a male God speaking to a male angel about the prayers for George Bailey in Bedford Falls, USA, on a snowy Christmas Eve. They decide to send trainee angel, Clarence Odbody, who is yet to acquire his wings. Clarence then watches how and why George Bailey is on the verge of jumping to his death off a blizzardy bridge into a black, fast-flowing river. Despite the urgency of the subject matter, the tone here is comic, almost cartoonish. The structural device of having Clarence watch the film of George Bailey’s life is crucial for a few reasons.

Most significantly, we watch George’s unfolding life — his bravery in rescuing his younger brother Harry from drowning when they were children, his thirst to escape Bedford Falls and see the world, his love for Mary Hatch and the community, his ambivalence about running the co-operative building and loan business — through Clarence’s eyes, through an observer’s eyes. This brings an important ironic layer to the narrative: we know that George is being watched by a kindly angel, and therefore is basically safe. Without this structural device, much of what happens would be very dark indeed: George’s rage and violence against his work, his wife and children would be extremely black.

This concept of having a kindly observer paying deep attention to our lives has become in recent years as a recognised therapeutic tool. Let me explain. In a number of spheres, but particularly in compassion-focused therapy, it has been shown that when people develop self-kindness strategies, where they learn to say kind things to themselves and treat themselves with kindness, and — vitally — to observe their own behaviours in a kind way, then they often cure themselves of chronic anxiety.

Therapeutic aspect two: The momentous effect of ‘reframing’ narratives

Along with Clarence Odbody we observe George Bailey’s life — which Clarence then proceeds to save, both literally and spiritually. First he jumps into the river, which distracts George from killing himself and makes him save Clarence. Then, after they’ve recovered, George tells Clarence that the world would have been better off if he hadn’t been born. Clarence then shows him — and us — what the world would be like if George Bailey had never existed. Bedford Falls would have become Potterville — owned entirely by the monopolistic authoritarian capitalist Henry F. Potter — and people would live in poverty and misery as a result, unable ever to own their own homes. George’s brother Harry would have died when he was a young boy because George wasn’t there to rescue him from drowning. That means that many people would have died in the Second World War because Harry wasn’t there to rescue them.

The chemist, Mr. Gower, is a broken man because George wouldn’t have been there to stop him putting poison in a patient’s medication. Other people, like Mr Martini, do not own their own home, but live in Potter’s slums. The place where the idyllic Bailey Park was, where people live happily in the savings and loan’s houses, is now a graveyard.

As George travels around Potterville, he gradually comes to accept, through various traumatic episodes, that he really doesn’t exist in this alternative reality. When he returns to the bridge, he pleads with Clarence to make him exist again: a wish which Clarence duly grants. The policeman, Bert, who in Potterville didn’t know George and was going to arrest him, now approaches George to see if he is OK. George is initially frightened that Bert will hurt him, but then realises that Bert knows who he is and cares for him. Having seen an alternative version, his view of reality is now entirely ‘reframed’. Clarence has acted as his therapist, and has reframed his reality for him in much the same way a good therapist can do, according to the Human Givens methodology. Reframing happens when a patient reconsiders their reality, seeing it more positively than before.

Therapeutic aspect three: The importance of gratitude

A vital aspect of reframing is learning to be grateful for what is positive in one’s life. The importance of gratitude has long been acknowledged in many spiritual traditions and increasingly in therapeutic ones too. After George has reframed his perception of reality, and understood his significance in the world he belongs to, he walks through it, feeling the miracle of his being alive and part of a community. He becomes aware that the very things that he used to hate are actually things he loves. The most striking example of this for me is his relationship with the broken banister in his home. It used to drive him crazy, a symbol of disorder which he loathed. But now he realises that it is emblematic of his home, his beautiful, ramshackle home which is full of love.

Therapeutic aspect four: The significance of understanding context

Franklin Delano Roosevelt became the 32nd American President in 1933, in the midst of the Great Depression. Immediately he had the job of trying to rescue the banking system, which people had come to distrust. ‘Runs’ on banks saw Americans pulling out their savings, and many banks had gone bust. The previous president, Herbert Hoover, had caused more problems by closing the banks at times when it looked like they may go bankrupt; this had the opposite effect of that intended, with people rushing to withdraw their money. Famously FDR took a different tactic, declaring a bank ‘holiday’ and held a ‘fireside chat’ on the radio with the American people, explaining to them that the banks relied on people’s co-operation, and that it was now an ‘unfashionable pastime’ to hoard money at home.

George Bailey gives a very similar speech to stop the folk of Bedford Falls causing his savings and loan business from going bankrupt. He saves the bank because he teaches his community about the importance of context: he helps them to understand the bigger picture; that we thrive when we help each other.

The whole film teaches this vital lesson: that we are not alone; that our communities flourish when we help each other.

Non-therapeutic aspect one: Attitudes to gender

The film very much promotes a post-Second World War attitude towards women. There is a rigid separation of the sexes in the film; men and women rarely interact. Men runs all the businesses, while women are at home. This is taken as a given. The most egregious example of the sexism of the film is when we learn that Mary, George’s vivacious, charming, intelligent wife, has become an ‘old maid’ in Potterville, and is working (horror of horrors) as a librarian.

Clare Coffey argues that the film ultimately undercuts its own sexism in its portrayal of Mary, who is the person who saves George — she persuades the citizens of Bedford Falls to bring their cash to the bank inspector at the end.

But even if you accept this point, the sexism of the film remains. For me, this is not a healing aspect for the modern audience.

Non-therapeutic aspect two: Its critique (or rather, acceptance) of capitalism

The film never ultimately questions capitalism and its inequities. Instead, it offers a vision of capitalism working if people co-operate with each other. Reading it in a contemporary manner, it is to a degree radical in its interrogation of monopolistic capitalism. Henry R. Potter could easily be one of the corporate oligarchs who wield so much power today. He is represented as psychologically irreparably damaged, and destructive to all those in Bedford Falls. However, the film never goes to the lengths of other films from that era such as The Grapes of Wrath (1940) or Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936).

Capra’s comedy was investigated as being possible Communist propaganda according to this website, but never formally designated as communist.

Summing up

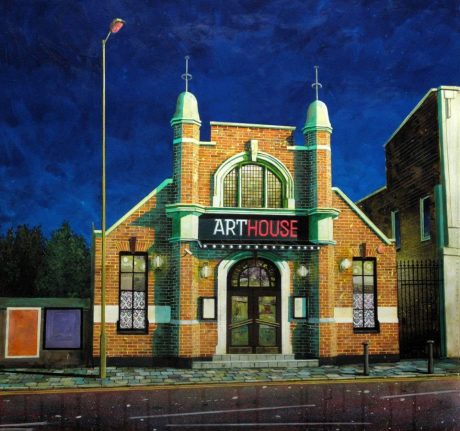

I saw the film again at the Crouch End ArtHouse this Christmas (for £5 which is very cheap for a London cinema). It was a cathartic experience, not least because the ArtHouse is a lovely, old fashioned cinema, with a screen which is just the right size, an ‘old fashioned’ size dare I say it, and the ambience is redolent of the 1930s and 40s.

To my surprise, I found myself crying at certain junctures: the moment where George realises that he will have to work at the bank when Harry returns home with his bride, the return to the bridge when he realises Burt is his friend. I’ve seen the film many times over the years, but it seems to have grown in power and relevance, despite its age and some aforementioned old fashioned elements. In particular, training to be a Human Givens therapist has provided me with a new perspective upon it because much of its content connected with the Human Givens approach in that the film advocates for depressed, suicidal people to reframe their stories, and see life more positively. Clarence is rather like a Human Givens therapist, guiding George to reframe his life and see what is right there, rather than what is wrong.