ONE: To tell our own story is to take control of our lives

Punchdrunk’s immersive theatre event, Viola’s Room, is narrated on headphones by Helena Bonham Carter, acting a script written by the novelist Daisy Johnson. The plotline is based on Barry Pain’s 1901 short story The Moon Slave, but has been updated by Johnson and Punchdrunk so that Viola has become modern-day child, from the same generation as Johnson. This is not a conventional theatrical experience, but a journey, which begins when — as a group of six — you are invited to take off your shoes, don a pair of binaural headphones and walk through a door, where you find yourself in a bedroom, clearly that of a young girl. It’s the 1990s: the headphones fill up with the sounds that create Viola’s world — music (the Smashing Pumpkins, Tori Amos’s Cornflake Girl) and the noises in the house and the outside world.

We become Viola, and then follow a thread of glimmering lights that lead us down a pillowy white tunnel into the mysterious world of Viola’s imagination and/or alternative life. This is where the link with Pain’s story happens. Presumably, Viola has read ‘The Moon Slave’, and has become Princess Viola, who has grown up in a gothic palace. She loves to wander through the palace’s corridors and rooms, gardens and grounds. At a very early age she learns from her parents that she is betrothed to Hugo, the prince. But when the time comes to marry him, she has second thoughts. When her parents die, she is abandoned, left to wander this world in more or less total isolation. She escapes from her engagement party, and finds herself in the palace’s maze, where she is compelled to dance until her feet are bloody. When her wedding day arrives, she does not appear at the altar, abandoning Hugo — instead entering the maze again, where she reprises her dance. When Hugo looks for her, there is no trace of her: all he discovers is the print of a cloven hoof in the sand near the great tree where she danced. As we leave Viola’s labyrinthine imagination, we are left with an overwhelming sense of freedom and mystery. Johnson’s story and the event itself invites us to take control of the narrative of our lives; to see that we have choices where no choices seem to be on offer.

TWO: Our lives are magical stories

I was, like so many people, mesmerised by the experience, and left the event in a daze. Getting the train home from Punchdrunk’s base in Woolwich, London was very different from my journey there: I had become hyperaware of the textures under my feet, the noises around me, the ever-changing smells, the quality of the light, the strange, artificial nature of the human and natural environment around me. I had become part of my own magical story.

THREE: There is a porous border between the artificial and the real

I have had the privilege to work with Punchdrunk Enrichment, which is the educational ‘wing’ of Punchdrunk. While they embody Punchdrunk’s values, they are separate to the extent that they work with schools and communities to bring the magic of Punchdrunk’s immersive experiences to children and teachers who ordinarily wouldn’t encounter them. I was working with i2Media at Goldsmiths and involved with evaluating the effectiveness of Punchdrunk Enrichment’s educational programmes. This meant that I saw some of the work that they did in schools, and undeerstood how miraculous it was. One grey day during the Autumn term of 2022, I followed a group of Year 3 pupils in a South London primary school walk down a corridor and find a strange door they’d not seen before. Some of them entered it, and discovered, like I was to realise a little later, that they were in an entirely different world; a magical ‘lost lending library’, choc full of strange books and fabulous miniature objects.

What was clear in working with this wonderful company was that Punchdrunk Enrichment, and I’m sure the Punchdrunk team too, see the real and imaginary worlds as porous, and that the imaginary world is as real to them as the so-called ‘real’ world. This, for me, is why their productions are so successful; there’s a power and conviction about their art which transcends much similar work. For example, their use of real materials and eschewing of digital computer graphics to create their experiences makes being in their creations unbelievably vivid. Every object, every silhouette, every tree, every window, every ceiling, every floor and every smell has its roots in the real world, because the imagination is palpable. I was struck by this when having the good fortunate to sit in on some planning meetings with Punchdrunk Enrichment; every member of the team believed absolutely in the world they had created.

FOUR: Our lives are immersive theatre

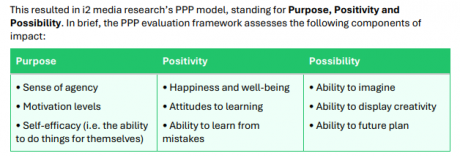

i2Media’s research shows that this approach has wonderfully positive effects for the children who experience it. From their research, they arrived at a way of evaluating the impact of arts-based work upon audiences and learners, which is summed up in their report in this way:

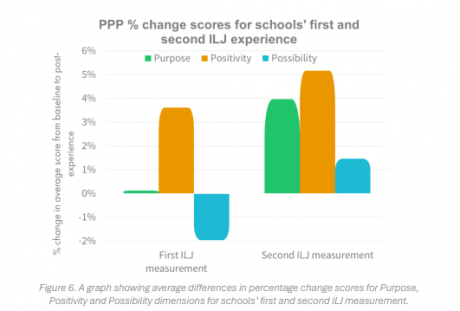

Applying this framework by deploying surveys with pupils and teachers in the schools which worked with Punchdrunk Enrichment arrived at many fascinating findings. The most significant statistical data was illustrated in this chart for me:

This chart shows that pupils at primary schools find experiencing Punchdrunk Enrichment’s immersive learning journeys as overwhelmingly positive, but on the team’s first visit to the school, the students’ ability to envision the possibilities of applying their learning and experiences is not clear to them. However, when Punchdrunk Enrichment visited the school a second time, the pupils could comprehend much more clearly how to apply their learning in other contexts and had a much greater understanding of the purpose of such an experience.

For me, having experienced both Punchdrunk Enrichment’s Immersive Learning Journeys and Punchdrunk’s Viola’s Room, I have come to learn that our entire lives are a form of immersive theatre. We live in our own tangled fairytales, and find meaning in them when we, like Viola, learn to see that we do have choices about how to live our lives, and that we can escape the imprisonment of hegemonic expectations and scripts.