This post introduces Ecologies in Practice and Learning: Arts Interventions in the Earth Crisis, an edited collection that brings together arts educators, practice researchers, curators and artists to explore ecological approaches to learning in a time of accelerating environmental crisis.

The book is concerned with how learning happens in, with and through ecological crisis. Rather than treating ecology as a topic to be taught, the contributors approach it as a lived condition that reshapes how people gather, attend, make meaning and take action. Across the collection, the arts are positioned not as decoration or illustration, but as vital methods for sensing, thinking and responding in damaged and unequal environments.

Each chapter contributes new understandings of arts-based processes that have the potential to enable reparative, future-changing interventions. These include practices developed in universities, schools, galleries, museums, theatres and community settings. Collectively, the chapters explore how creative work can generate awareness, assemble publics, and support forms of protest and care in the context of the Anthropocene.

A key strength of the book is its commitment to practice-based research. The contributors do not write from a distance. They reflect on projects that unfold in real places, with real participants, and often under conditions of constraint, precarity or environmental harm. Readers are encouraged to engage in their own regenerative creative processes, guided by authors who have tested these approaches in educational and cultural contexts.

The book also has a strong ethical orientation. It seeks to assist more equitable educational practice in environments that have been compromised or devastated by extractive economies, climate change and social injustice. In doing so, it speaks directly to educators, researchers and students who are developing ecological arts projects and looking for models that are both critically rigorous and socially engaged.

The Parklife chapter

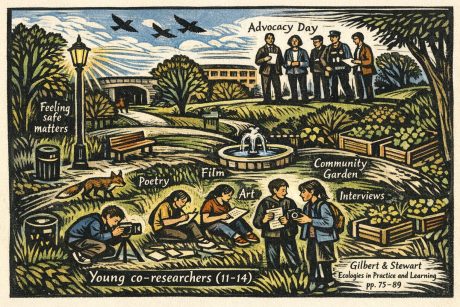

My chapter, co-authored with Anna Stewart, appears on pages 75–89 and is titled How can we help young people improve their local environments? How can they become agents of change? It grows out of the Parklife project, a collaboration between university students, school pupils and local communities.

The chapter focuses on young people aged eleven to fourteen who became co-researchers into a local park next to their school. Using creative and participatory research methods such as poetry, visual art, photography, film using 360-degree cameras, surveys and interviews, the young researchers explored questions of safety, ecology, care and belonging.

Crucially, the research did not stop at expression. The young people presented their findings directly to councillors, park managers and community organisations. The creative outputs generated powerful affective responses and led to tangible changes in the park, including improved lighting, better litter management, a new water fountain and the creation of a community garden.

The chapter argues that creative research can generate what we describe as affective flows, moments where feeling, insight and action align. It challenges deficit narratives about young people in public space and reimagines parks as classrooms without walls, where learning, citizenship and environmental care are deeply intertwined.

Methodologically, the chapter draws on posthuman and new materialist theory, understanding parks as assemblages of human and non-human actors. It makes a case for research that is collaborative, rhizomatic and non-hierarchical, where young people’s situated knowledge is valued alongside academic expertise.

Read and download

You can read and download the full copyright-free chapter here:

Springer book page:

https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-031-82338-1

Goldsmiths research repository:

https://research.gold.ac.uk/id/eprint/40154/