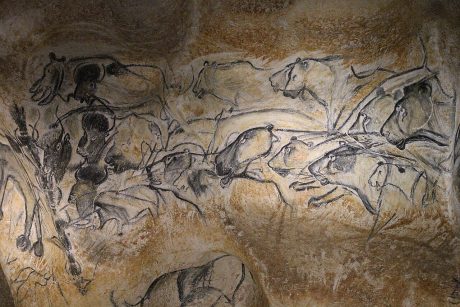

1. Cave Lions: speaking to time 30, 000 BC

The Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave in France contains some amazing cave paintings of lions and bison. I’m particularly interested in them from the point of view that they are some of the first known pictures produced in the world, possibly created over 30,000 years old. Think about that for a moment! Human, history at a stretch, began approximately 5,000-7,000 years ago with the emergence of city states in Mesopotamia and the first Egyptian civilisations. These paintings are six times older than our most ancient civilisations. And yet, in many ways, the art speaks to us more directly than much of the work created in ancient Egypt and Iraq. Why is this? First, it is representational; the animals are recognisably animals, and they have a dynamism about them which is very modern. The lions in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc are predatory, hungry, threatening. The paintings have the quality of a thriller. You can imagine stories being told about them, and around them. Indeed, they almost certainly were. Fires lit the caves with trembling light, and human feet, including children’s feet, walked through their mysterious environs.

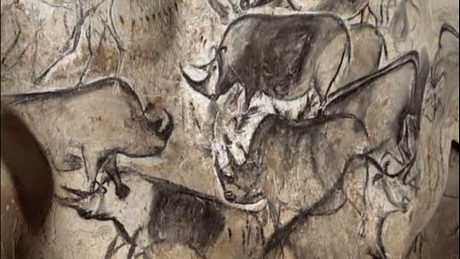

For me, this is where the story of publishing begins. Why? Well, it’s because here we can see clear evidence of art being produced for specific audiences. This work is trying to communicate with the viewer; it has a narrative quality. Look below at the drawing of two rhinoceroses interacting; again, there is a sense of a relationship between them, an enmity possibly, but certainly a story to be told about them.

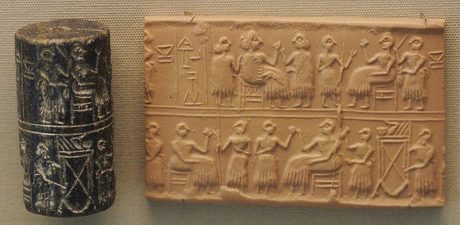

2. Cylinder seals: speaking to status 2600 BC

Cylinder-seal of the “Lady” or “Queen” (sumerian NIN) Puabi, one of the mais defuncts of the Royal Cemetery of Ur, c. 2600 BC. Banquet scene, typical of the Early Dynastic Period.

The cylinder seals which you can see in the photo above, taken in the British Museum, served as administrative seal, and also as jewellery and magical amulets. They, like the paintings of the wild animals in the Chauvet-Pont-d’Arc Cave, tell a story, but they also serve another important purpose in the story of publishing. They are a key marker of status. They would have been expensive to make both in terms of materials and also in the labour that it would take to make them. They would have been rolled onto wet clay tablets, again costly objects. With the advent of agriculture (roughly 12,000 years ago), human beings began to stay in one place, and resources were distributed differently. Hierarchies developed with the emergence of the concept of property ownership, and a class of people who were deemed to have access to vital knowledge assumed power (Patel and Moore 2018). Writing and literacy played a crucial role in helping shape a priestly class which had access to knowledge, those who could not read did not have. The cylinder seals celebrated the power of the person who owned, though not necessarily created, the seal. This kind of publishing continues to provide a marker of power and status.

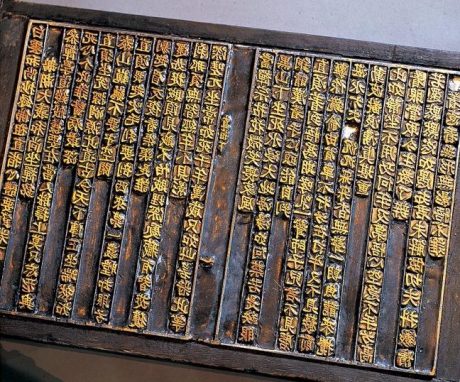

3. Movable type: China versus Europe 1050AD

The Chinese invented movable type in roughly 1050AD, an invention which the goldsmith Gutenberg in Germany (1450AD) learnt from, but as Angeles (2017) points out:

The European adoption of printing was much faster than China’s, and almost entirely led by the private sector. In comparison, the state was the major player in China from the invention of printing up until the middle of the sixteenth century, when the output of private firms finally became dominant. It took Europeans about 50 years to set up more than 200 printing shops across the continent, whereas a similar number was reached in China only during the Southern Song dynasty, no less than 300 years after the invention of block printing during the Tang. (33)

The rise of mercantilism in Europe (Moore and Patel 2018) led to those who owned and ran printing presses becoming publishers and spearheaded massive cultural and religious change. The Reformation, whereby many countries and groups of people in Europe separated from the Catholic church, was, in part, fuelled by the printing press.

Movable type, printing press technology and the lowering in costs of making paper led to the Bible being translated and printed for anyone to read; priests were no longer the sole custodians of God’s truth. The publishing of the Bible meant that people could have an unmediated relationship with the words of the Bible. This idea is a vital idea to understand in terms of the rise of publishing and so much else in the Western world. Concepts such as fundamental human rights, the right to freedom, education, self-expression, autonomy, justice emerge from this revolutionary notion.

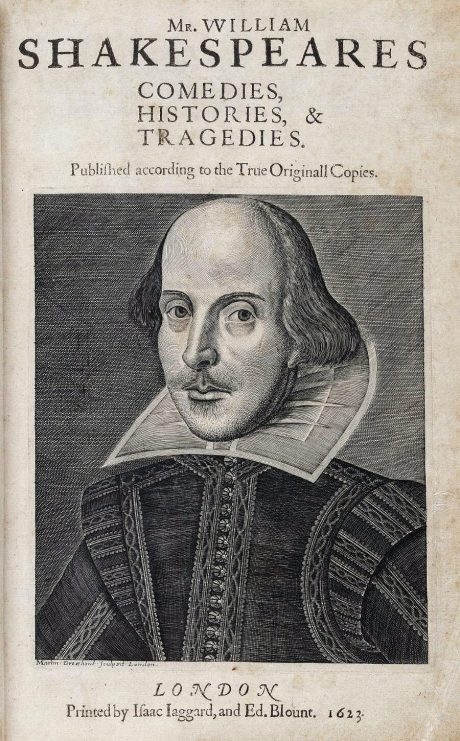

4. Shakespeare’s first folio 1623

Shakespeare’s plays were already very popular as individual printed pamphlets during the era when he wrote and performed in his plays, roughly from 1590-1620. They could be purchased for the equivalent of £6 in today’s currency. The First Folio, a collection of his most popular plays at that time, was compiled by John Heminges and Henry Condell who put together many plays into one bound volume, using the aforementioned movable type technology. Booksellers Edward Blount and the father/son team of William and Isaac Jaggard, who were members of the Stationers Company, a trade guild in the City of London, published the book. The First Folio cost the equivalent to £174 in 2023 for an unbound copy, while a calfskin edition cost the equivalent of £232 in 2023. This was largely because paper was so expensive at this time.

The First Folio is considered, alongside the Bible, to be one of the most important books published in the global north. Ultimately, it led to Shakespeare’s works being distributed across the world, and helped form, over a hundred years later, the myth of England’s literary heritage, a myth which was mobilised to colonise other countries. In the 19th century, politicians such as T.B. Macauley would use Shakespeare’s work as political weapons, claiming that the indigenous people of Britain’s colonies needed to learn his work in order to be civilised. By then, the technologies of the Atlantic slave trade and industrialised printing processes had both directly and indirectly led to the cost of book production to be much cheaper. In 1890, an average bound book cost roughly £15 in today’s currency. The publishing industry, in the form of private printing presses and companies, was an important engine for colonialist expansion in the United Kingdom on many levels: it promoted the supposed superiority of English culture, it disseminated its propaganda, it brought employment to millions of people across the globe both directly and indirectly: booksellers, writers, editors, printers, publishers, educators, transporters etc.

5. William Blake’s printing press 1787

One writer who railed against the industrialisation of printing processes was the poet and artist William Blake. His work struggled to find a mainstream publisher for a number of reasons: it was both against the grain in its approach, and politically unpalatable. Blake grew up in London and was part of a now lost artisan class: craftspeople who were shaped by artistic and spiritual values informed by a particular strain of Protestantism. This was the class that, in part, fuelled the Reformation in Europe and the Civil War in England, when Charles I was executed and replaced by Thomas Cromwell in 1648. According to the historian E.P. Thompson, Blake’s parents may well have been Muggletonians, a now defunct Protestant sect who believed in nudism, free love and a radical interpretation of the Bible which labelled the patriarchal God of the Old Testament as the devil. While Thompson’s history may be speculation, what is certain is that Blake was the inheritor of a rich religious and artistic tradition that was under threat. He recognised this, and set up his own way of publishing books after his beloved brother Robert died in 1787. The ghost of Robert visited William in a dream, and showed him how to print both pictures and text together using an innovative technique called relief etching. As a result, Blake was able to use his own printing press to create all of his books from that time onwards, which included the Songs of Innocence and Experience and his Prophetic Books. In these works, Blake railed against the evils of the slave trade, the treatment of the working classes, industrialisation and the education system. His work remains challenging and pertinent today.

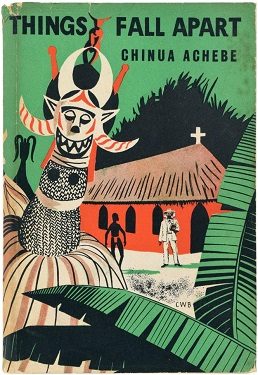

6. Things Fall Apart 1958

The Nigerian writer, Chinua Achebe, had his debut novel Things Fall Apart published by William Heinemann in 1958. Written in colonial Nigeria in the 1950s, Achebe sent the manuscript of the novel to be typed in England for £22 (the equivalent of £524 now), and then onto a literary agent who received a number of rejections from UK publishers who saw no financial potential for an African novel. Eventually, it was picked up by Heinemann, and was warmly received with patronising if positive reviews in the British press.

It is a haunting tale of a flawed African leader, Okonkwo, who lives in the village of Umuofia. He has to deal with difficult, warring neighbouring villages, and the arrival of British missionaries and colonists. He is a patriarchal, proud man who is richly and ironically characterised by Achebe. The title of the novel, taken from Yeats’ poem of the same name, is appropriate because we witness in the novel how and why colonialism can destroy the fabric of a colonised society. Achebe’s approach is empathetic to the people, but condemning of the violent structures that led to people’s dehumanisation, humiliation and ultimately deaths. The novel sold 2,000 copies on publication (quite a good amount for a novel then), but has gone to become one of the most significant literary works of the 20th century because of its analysis of colonialism, and its rare viewpoint.

7. WordPress 2003

I guess I could have chosen any amount of objects which might represent the emergence of the internet, and the revolution in publishing which began to happen in the early 1990s with the emergence of the world wide web. I wanted to focus upon WordPress because of its importance to me as a writer. I had struggled during the 1990s to both write novels and then publish them. I wrote four novels during my spare time while also teaching English, English as an Additional Language and Drama full-time in various London state secondary schools. I yearned to be published by a mainstream publishing house; this, to me, represented the height of success. I had done the MA in Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia in 1990-91, where being published by the likes of Faber and Faber was presented as a vital stepping stone to literary success by the head of the programme, Professor Malcolm Bradbury. Many colleagues from that time went to do this, but I didn’t. However, in 2003, when I had all but given up on the dream of being published, I met a publisher, Rebecca Nicholson of Short Books, who encouraged me to write about my teaching experiences. This led to me writing I’m A Teacher, Get Me Out of Here (2004), and thinking carefully about my public persona. It was just at the time when WordPress were starting their blogging apparatus on the internet. Working with Andrew Staffell of YesWeWork, I set up this blog in 2005, where I put much of my writing. At that time, I was getting many commissions to write for national newspapers and magazines. I posted my articles on this blog, and built up over the years a big archive of my work. I am so glad I did. If I had not done so, much of my work would have been lost. The arrival of social media sites like Facebook (2005) distracted many writers I feel (well, I suppose it depends what you want from a publisher). It’s very difficult to access your own work from the past from social media outlets like FB, X, Instagram etc, but this is not true of WordPress, which provides a decent archive work. For this reason, I feel that my WordPress site has become my home on the internet. To the extent that anything is safe, it feels a safe place to showcase and publish my work. It provides a degree of control and autonomy which I think I’ve always wanted as a writer.

Discussion

During their seminar which explored the methodologies which inform the pedagogy on their module, The Publishing Industry, the MA students in Creative Writing and Education at Goldsmiths discussed their understanding of the complexities of the publishing industry.

Two students presented on their reading for the week, and brought up the issues raised in this blog and others.

They delivered a fantastic presentation on the History of Publishing, diving into how the myth of the authorial genius came about. Apparently, writers like Coleridge and Kerouac claimed their masterpieces just magically popped into existence—poof! But research reveals that these literary Houdinis actually put in some serious elbow grease on works like “Kubla Khan” and “On the Road.” So much for spontaneous genius; turns out even legends need a little sweat equity!

This knowledge nurtures their development as both writers and educators, supporting them with care and guidance as they navigate their future paths.

Understanding the publishing industry is not just an academic exercise for MA students in Creative Writing and Education at Goldsmiths; it’s a vital component of their development as writers and educators. By contextualizing their craft within the realities of publishing, these students can better navigate the complexities of bringing their work to a wider audience. This understanding serves as an invaluable teaching tool, allowing them to share insights with future writers about how to approach submissions, marketing, and networking effectively.

Moreover, knowing the ins and outs of the publishing world empowers writers to harness it strategically. They can utilize industry trends to inform their writing projects or adapt their styles to meet market demands without compromising their artistic integrity. However, there’s an essential caveat: for creativity to flourish, writers must feel happy and relaxed. Stress and anxiety can stifle inspiration; thus, creating a supportive environment that prioritizes mental well-being is crucial.

References

Angeles, L. (2017). The great divergence and the economics of printing. The Economic History Review, 70(1), 30–51. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45183273

Patel, R. and Moore, J.W. (2018) A history of the world in seven cheap things a guide to capitalism, nature, and the future of the planet. London ; New York: Verso.

Leave a Reply