To my mind, Creative Writing (CW) currently languishes like a frightened animal in one of the curriculum’s darker alleyways, shivering and rather worried about its prospects.

Having been an English teacher for twenty-five years in various comprehensives and now a Lecturer in PGCE English at Goldsmiths, which involves visiting many schools, I have both taught Creative Writing to ages 11–18 years and trained beginning teachers to do so as well. This has made me aware that authentic Creative Writing is an “endangered species” in schools. The axing of the Creative Writing A Level was a big body-blow; this excellent A Level, set up by NAWE and AQA, was just beginning to generate genuine interest in the subject amidst not only English teachers but also Senior Leaders, who saw the value of it for students who wanted something beyond the more analytical English A Levels – English Literature, English Language, English Literature/Language. The shutting down of the A Level (with the last assessments in 2017) means that Creative Writing is losing much of its visibility within schools.

This said, the CW component of the new English GCSE has pushed story-writing to the forefront of the minds of many English teachers, who are currently trying to work out what the specifications are requiring students to do in the exam, which will be first assessed in the summer of 2017. As we all know, the quality of CW is notoriously difficult to measure, particularly in exam conditions. Enervating English teachers further is the fact that English GCSE is, along with Maths, the most significant qualification not only for students, but also for schools because it is “double-weighted” for league table purposes; a set of poor GCSE English results can affect a school’s overall ranking drastically. Perhaps not surprisingly, this has led, in my view, to panic in some quarters, with English students (and less experienced teachers) seeking the magic CW “recipe” to boost their grades; this, in turn, has led to a growing cohort of pupils following various dubious “formulas” in order to write the “top grade” story.

The lessons I’ve observed where I’ve seen teachers attempting to provide students with prescriptive plans are not successful. I saw one lesson where a teacher told his students to include five nouns, seven “wow’ adjectives and three “great” adverbs in their story, as well as a variety of sentence structures. The writing produced was lacklustre and would not have achieved high marks in the GCSE.

Examples of good practice

There is, though, some light in the dark alleyway. Simon Wrigley and Jeni Smith (2012) run the National Writing Project (NWP) in England and have been very successful at encouraging teachers to be writers outside the confines of school, and bring their understanding of their writing processes into the classroom. Wrigley and Smith’s research indicates that when teachers write with their students and have a better understanding of how creative writers shape and work on their material, they are much more effective at teaching CW.

But the NWP, though growing in popularity, remains a relatively small movement. Indeed, there has never been a more important time for professional writers to promote their creative approaches in the secondary English classroom. NAWE has led the way in both researching and disseminating outstanding practice. Its report in the ecology of writers in schools, Class Writing (Owen and Munden 2010) offered wonderful advice, stressing in its conclusions the importance of students being taught to re-draft their work properly, for schools and professional writers to plan carefully what they might do together, and for both writers and teachers to be consistently well trained about relevant teaching and learning strategies. Above all, it urged schools, English departments and writers to come together to develop what might be termed “creative cultures” which embed innovative approaches to English.

My experiences

I have been a creative writer since my teens, and have now published many books, including one novel, The Last Day of Term (2011). Until quite recently, I had always kept my identities as English teacher and creative writer quite separate, but being a member of NAWE, participating in the NWP workshops and doing a PhD in Creative Writing at Goldsmiths has changed me. I now see the importance of bringing creative writing systematically into secondary schools with teachers leading by example and showing how they write themselves; my own research shows that this generates reciprocity with students wanting to share their own work more willingly in the classroom context (Gilbert 2012).

At last year’s NAWE conference and in a previous issue of Writing in Education (No. 67), I outlined some creative strategies for teaching “classic literature”, suggesting ideas such as predictions, role play and visual organizers in order to help students think imaginatively about challenging literature. My presentation at this year’s conference and this article has a different emphasis, exploring the vital importance of generating the right emotional atmosphere for effective creative writing and the tactics that might be employed to do this.

What actually is creativity and what are the conditions that best nurture it?

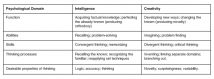

Much research (Wrigley and Smith 2012; Owen and Munden 2010) indicates that anyone teaching creative approaches needs to grapple with the thorny question of what creativity actually means to them. In his book, Creativity in Education and Learning, Cropley produces a helpful table (above) which outlines some of the possible differences between intelligence and creativity (2004: 26).

I have found Cropley’s chart very useful for orienting my teaching because it enables me to speak about what creative writing both is and is not. Its primary purpose is not to produce factual knowledge or “problem-solve”; this is useful to bear in mind because many English teachers believe they are “doing CW” by asking students to write things like diary entries based upon characters they are reading about; teachers then mark these entries to assess how well their students have understood the story. Cropley’s taxonomy tells us that in this situation they are marking the diary entries to gauge students’ understanding and intelligence, not their creativity.

However, if they were to mark it for creativity, they would be examining how the diary entry contains “divergent thinking” and “novelty”. This means that a piece that might get high marks for understanding could attain low marks for creativity because there might be very little evidence in the diary entry of “new thinking”. Conversely, a diary entry that might score highly for creativity may well score poorly for revealing understanding of the text.

It is an obvious point, but very important to consider; if teachers want to promote creativity they need to stress the importance of saying something new or different. And yet, my own experiences and much research, even by official organizations such as Ofsted (2012), indicates that most English lessons focus upon developing students’ convergent thinking and reapplying set techniques, rather than discovering new domains of knowledge. While teachers may feel more secure in helping students problem-solve rather than problem-find, there is a cost for society. As Cropley says:

Creativity in children is necessary for society. Finally, creativity offers classroom approaches that are interesting and thus seems to be a more efficient way of fostering learning and personal growth of the young. Creativity helps children learn and develop. (2004: 28)

Mindfulness and Creativity

An exciting development in a number of schools recently is the promotion of a therapeutic technique called “mindfulness”; this is a simple meditation process whereby students are encouraged to shut their eyes and concentrate upon the flow of their breath for a few minutes at various times during the week, usually in their tutor periods (MiSP 2016). It is primarily being used to help students deal with anxiety and stress. This August, the Big Lottery Fund has provided £54m for some properly tested pilots to be rolled out in various boroughs across the country (Big Lottery Fund 2016) because there is a growing body of evidence that the strategy significantly helps with mental well-being (Thornley 2016).

Having been sceptical of such claims, it wasn’t until I began to meditate myself that I began to understand that mindfulness strategies can really aid creativity. Wordsworth’s famous definition of poetry as “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings” which “takes its origin from emotion recollected in tranquility” (Wordsworth 1800: xxxiii) is relevant here: I found that I was writing much more fruitfully having meditated before I wrote. I felt freer and less conflicted about writing. So I trialled mindfulness as a teaching strategy for CW and found the results were surprising; I worked with a number of Year 8 classes in a deprived inner-city school, asking them to meditate at the beginning of each class and do some “free writing”; they could write what they wanted for a few minutes, the only rule was that they had to keep writing. The results were very positive after some initial grumblings. Behaviour in those classes significantly improved at the beginnings of lessons because most students enjoyed the routine of the meditation, and they began to see writing as a liberating thing. At the end of the project, many pupils said that they hadn’t realized writing could be a place where they could release their feelings, or create things they liked such as raps, rhyming poems, violent descriptions, ditties etc.

Now I ask all my classes (postgraduate students too) to begin our session with a few minutes’ meditation and free writing. Even highly educated postgraduates have appreciated this space to think and write laterally. As Danny Penman in his book on Creativity and Mindfulness says: “you need a calm, open and disciplined mind that can gather and integrate new ideas and information” (2015: 43).

Although there are no doubt therapeutic benefits for participants doing this form of mindfulness, I do not run the meditation sessions primarily for therapeutic purposes (as is the case in most schools) but because I want to generate the optimal conditions for creative work. CW is best nurtured in calm, relaxed environments; it is usually “emotion recollected in tranquility”.

Furthermore, there is a very strong “meta-cognitive” element to mindfulness; the practice is largely about observing one’s thoughts and feelings from a cognitive distance. This is tremendously useful for the creative writer because this is largely what we do: we shape and mould thoughts and feelings into artful language. Mindfulness gives the creative writer the cognitive tools to think about their emotional processes.

This said, my research and the research into mindfulness in schools is in its infancy, so one must be guarded about huge claims for it. If you are interested in it, do get in touch with me (email provided below).

The atmosphere of the creative writing class

As I have argued and as Wrigley and Smith illustrate in their research, it is very important to establish the right atmosphere for creative writing. The National Writing Project has a superb manifesto (and poster) called The Rights of the Writer. These are:

1. The right not to share

2. The right to change things and cross things out

3. The right to write anywhere

4. The right to a trusted audience

5. The right to get lost in your writing and not know where you’re going

6. The right to throw things away

7. The right to take time to think

8. The right to borrow from other writers

9. The right to experiment and break rules

10. The right to work electronically, draw or use a pen and paper

(Wrigley 2014)

At the heart of this manifesto is the vitally important concept that creative writing does not flourish in fear-filled, exam-obsessed contexts and that many young writers need to develop their self-esteem in order to do their best work. They need a space where they can say to their peers that they are unsure about something or concerned that they may have made a mistake. This means creating a “no blame” atmosphere so that children don’t feel frightened to admit it if they don’t understand.

CW teachers can play a big role in creating these sorts of atmospheres. For example, they could strategically share some of their uncertainties and doubts. One thing I’ve found works very well is when I’ve articulated my thinking processes. I’ve regularly shared my thoughts and feelings as I’ve written a poem or story in the class with my students, saying things like “Oh hang on a minute, I am not sure what might happen next, maybe I’ll try this piece of dialogue etc… But is this not right? Maybe I should try this…” This has made students realize that there is no secret recipe for Creative Writing, but only an ongoing process of creating, reading through work, sharing it with other people if appropriate, assessing feedback and re-drafting it.

Using objects to stimulate Creative Writing

Once the CW teacher has established the right context – a “no-blame” atmosphere if you like, through using strategies like mindfulness and outlining the rights of the writer – he/she is in a stronger position to ask students to share their personal thoughts and feelings; this nearly always produces a higher quality of writing. A great way of stimulating original ideas is to encourage students to bring in objects which have been important to them in their lives. You could ask students to tell their life stories in ten objects, or to write about places they like by bringing in objects which evoke that place.

As an initial step, encouraging meditation and free writing on the object works well to unlock people’s thoughts. Paradoxically, free writing often produces some of the best writing, because students are much less inhibited and feel freer to explore bizarre ideas, situations and memories.

After the free writing, the CW teacher could stimulate discussion about the objects by encouraging students to share their ideas/memories about the objects in pairs or small groups. Then students could be asked to make notes about the objects, using the five Ws to stimulate their note-making:

1. What precisely is the object? What is important about it for you? What qualities does it have that you like?

2. Where did you first see it and why? Describe the setting vividly.

3. Who is the object important to and why? Who gave it to you and why?

4. When did you first come across it and why? Describe the series of events that led to you finding it etc.

5. Why is it still important to you?

Encouraging students to hold their objects and further meditate upon their textures, smells, tastes, and visual nuances really helps them discover new things about them. They could then perhaps imagine actually being the object and write a “personification” poem/passage in which they write the object’s narrative. This really boosts lateral thinking.

As many CW teachers know, there are many other things that can be done with objects, but I have offered these suggestions as a way to show that mindfulness/ free writing can aid personal writing. The crucial thing about using students’ own objects is that they have ownership of the subject of their writing. Students can bring their own cultures into the classroom by using objects, and learn about other people’s worlds as well.

Conclusions

In a section called “Flow and Learning” in his book Creativity: Flow and the Psychology of Discovery and Invention (1997), Mihalyi Csikseztmihaliyi stresses the importance of humans finding states of “flow” which is achieved when they undertake “painful, risky, difficult activities that stretch the person’s capacity and involve an element of novelty and discovery” that cultivates an “almost automatic, effortless, yet highly focused state of consciousness” (110). I would like to argue that some of the strategies I have written about here assist with the promotion of “flow”; techniques like mindfulness, free writing and the use of objects to help students feel less anxious about CW, and to stimulate new ways of thinking and feeling about themselves and their lives. The overall learning objective here (to use teacher-parlance) is to foster lateral thinking and Csikseztmihaliyi’s conception of “flow”: to allow students an affective space where they can both concentrate intensely upon their writing but also feel relaxed and calm. If we are to reinvigorate the status of CW in schools, we can do no better than to return to Wordsworth’s guiding precept of poetry being “emotion recollected in tranquility”.

References

Big Lottery Fund (2016) Pupils to get mental health support in schools through Lottery £54 million. [Online]

Available at: https://www.biglotteryfund.org.uk/ global-content/ press-releases/england/200716_eng_ pupils_get_mental_health_support_in_schools [Accessed 21 September 2016].

Cropley, A. J. (2004) Creativity in Education and Learning. Abingdon: Routledge.

Gilbert, F. (2011) The Last Day of Term. London: Short Books.

Gilbert, F. (2012) ‘But sir, I lied’ – the value of autobiographical discourse in the classroom. English in Education, 46 (3), 198–211.

Gilbert, F. (2015) Creative Classics. Writing in Education, 67, 40–48.

Smith, J. and Wrigley, S. (2012) What has writing ever done for us? The power of teachers’ writing groups. English in Education, 46 (1), 70–84.

MiSP (2016) Mindfulness in Schools Project. [Online]

Available at: https://mindfulnessinschools.org/

[Accessed 20 September 2016].

Owen, N. and Munden, P. (2010) Class Writing: A NAWE Research Report into the Writers-in-Schools Ecology. York: NAWE.

Ofsted (2012) Moving English Forward. [Online] Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system /uploads/attachment_data/file/181204/110118.pdf

[Accessed 19 September 2016].

Penman, D. (2015) Mindfulness for Creativity. London: Piatkus.

Thornley, C. (2016) Only schools can reverse Britain’s mental health crisis in children. The Times, 16 May.

Wordsworth, W. (1800) Preface to the Lyrical Ballads. The Lyrical Ballads. Bristol: T. N. Longman & O. Rees.

Wrigley, S. (2014) The rights of the writer. [Online]

Available at: http://www.nwp.org.uk/nwp-blog/the-rights-of-the-writer [Accessed 22 September 2016].

Francis Gilbert was a teacher for twenty-five years in various UK state schools. He is the author of many books about education, including I’m A Teacher, Get Me Out Of Here (2004), Parent Power (2007) and The Last Day of Term (2011). He currently lectures in PGCE English at Goldsmiths. His new novel, Who Do You Love, will be published by Blue Door Press in January 2017.

This article was first published in Writing in Education No. 70, Autumn 2016.

Leave a Reply